Introduction To Runes

Last Updated: September 19th, 2023

By: Mark Stevens

Introduction To Runes

Those seeking counsel often utilize runes, an ancient sort of oracle. Runes have a lengthy history, extending back to ancient Germanic and Nordic civilizations, and Runes are still extensively used today. Anyone can get a rune reading, but learning how to utilize them yourself is far more exciting. In this introduction to runes, we go over the very basics of runes and help you to figure out if you would like to know more.

Contents

What Are Runes?

Runic alphabets were the first writing systems devised and utilized by the Norse and other Germanic peoples. The runes served as letters, but they’re much more than that in the modern sense of the word. Each rune was a pictographic sign of some cosmic principle or force, and writing a rune was an act of invoking and directing the force it represented. Indeed, the term “rune” denotes both “letter” and “secret” or “mystery” in every Germanic language, and its true meaning, which likely predates the development of the runic alphabet, may well have been essentially “hushed communication.”

Each rune had a name that alluded to the philosophical and magical importance of its visual shape as well as the sound it represented, which was often the first syllable of the rune’s name. The T-rune, for instance, is named after the god Tiwaz and is called *Tiwaz in Proto-Germanic (known as Tyr in the Viking Age). Tiwaz was thought to live in the daytime sky, hence the T-visual rune’s form is an arrow pointing skyward (which undoubtedly also alluded to the god’s significant involvement in war). The T-rune was frequently carved as a solo ideograph, separate from the inscription of any specific word, as part of war spells.

In the very same manner that the word “alphabet” derives from the initials of the first two Semitic letters (Aleph, Beth), the runic alphabets are named “futharks” after the first 6 runes (Fehu, Uruz, Thurisaz, Ansuz, Raidho, Kaunan). There are three main futharks: the 24-character Elder Futhark, the first fully-formed runic alphabet, whose development began in the first century CE and was completed around the year 400; the 16-character Younger Futhark, which started to deviate from the Elder Futhark around the initial stages of the Viking Age (c. 750 CE) and later replaced that older alphabet in Scandinavia, and the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (33 characters), which was eventually added to the Elder Futhark in England. The Elder Futhark’s twenty-four runes were separated into three ættir (Old Norse, “family”) of eight runes each on some inscriptions, although the meaning of this division is unknown.

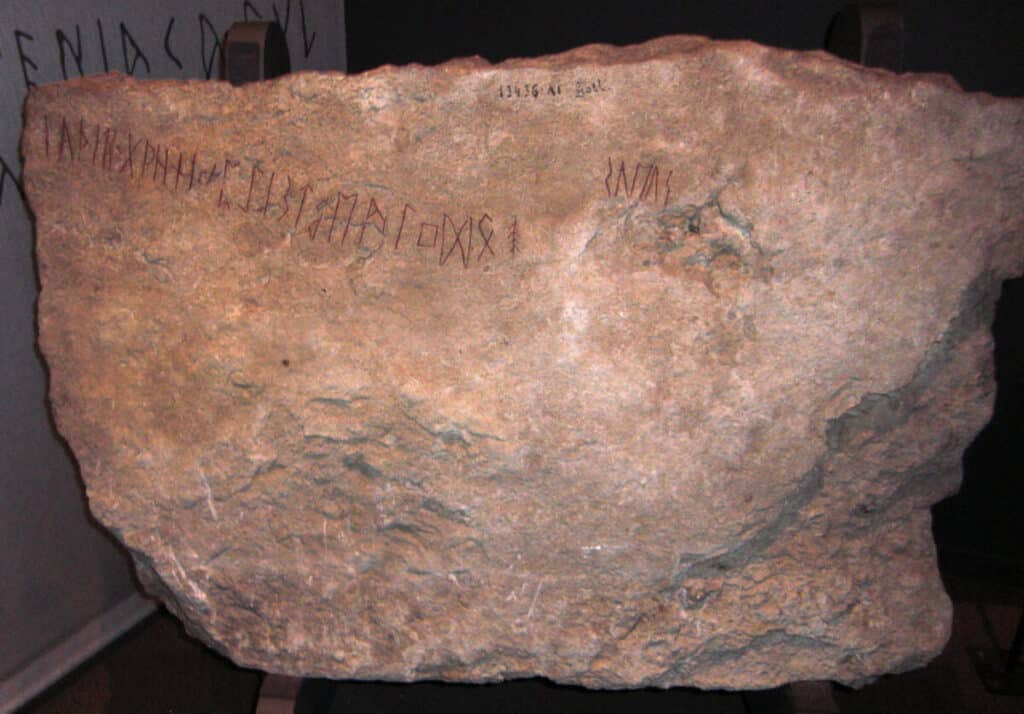

Rather than being drawn with ink and pen on paper, runes were typically carved into stones, bones, wood, metal, or another similarly hard surface. This explains their angular, pointed shape, which was ideal for the medium. The three “Rune Poems,” records from Iceland, Norway, and England that provide a short verse about each rune in their respective futharks, provide most of our present knowledge of the meanings attributed to the runes by ancient Germanic peoples.

The Origin Of The Runes

While runologists disagree on many specifics about the historical beginnings of runic writing, they all agree on a broad outline. The runes are said to have been evolved from one of the various Old Italic alphabets used by Mediterranean peoples living to the south of the Germanic tribes in the first century CE. Earlier Germanic religious symbols, such as those seen in northern European rock engravings, are thought to have influenced the script’s evolution.

The Meldorf brooch, which was made in the north of contemporary Germany around 50 CE, has the earliest possible runic inscription we know of. However, the inscription is obscure, and experts are split on whether the symbols are runic or Roman. The Vimose comb from Vimose, Denmark, and the Øvre Stabu spearhead from southern Norway, both dated to around 160 CE, including the first unequivocal runic inscriptions. The first known carving of the whole futhark (alphabet), in order, dates to around 400 CE on the Kylver rock from Gotland, Sweden.

The propagation of writing from southern Europe to the parts of northern Europe most likely occurred through Germanic warbands, the major northern European army institution at the time, who would have come into contact with Italic writing directly during wars against their southern neighbors. This view is backed by the god Odin’s long affiliation with runes, who was the divine model of the human Warband commander and the unseen sponsor of the Warband’s actions throughout the Proto-Germanic period. Odin was already established as the prominent god in the pantheons of several Germanic tribes by the first century. For our purposes, it doesn’t matter whether the runes and the Odin cult developed simultaneously or if the latter came before.

However, from the viewpoint of the ancient Germanic peoples, the runes did not come from a commonplace source like the Old Italic alphabet. The runes were never “created,” but rather are everlasting, pre-existing powers that Odin found after a grueling experience. Yggdrasil, the world tree in the center of the Germanic universe, whose branches as well as roots hold the Nine Worlds, is undoubtedly the tree through which Odin hangs himself. The Well of Urd, a source of tremendous wisdom, is located directly beneath the world tree. The runes themselves appear to have made their home in its waters. As a result, there is a clear link between the Well of Urd, the runes, and wizardry – specifically, the Norns’ (female beings from Norse Mythology who create and control fate) capacity to carve the destinies of any and all beings.

After Odin found the runes by ritually committing himself to himself and fasting for nine days while gazing into the depths of the Well of Urd, it is likely that he was the one who taught the runes to the very first human runemasters. His symbolic sacrifice was most likely duplicated in initiation rites during which the person learned the wisdom of the runes, but no solid evidence of such a practice has survived to the present day.

What Can You Do With Runes?

The runes can be utilized to assist you in navigating obstacles or issues, as well as to predict what is going to occur. They’re not a sort of fortune-telling, and they don’t provide you specific answers or guidance; instead, they present several variables and indicate how you may react if the event occurs. Runes are recognized for pointing you in the right direction but leaving you to figure out the specifics, and this is where intuition comes in handy.

Runic readers recognize that the future isn’t predetermined and that people have the freedom to choose their own direction and act independently. So, if you don’t like the advice given by a rune reading, you have the option to change your path or course, and take a different route. Runes can be applied to a variety of situations. For instance, if you’re in a position where you just have a limited amount of knowledge or can only see a partial image, consulting the runes can be beneficial.

It’s not fortune-telling when you use the runes. The notion behind how runes function is that your unconscious and conscious thoughts are concentrated while you ask a question or consider an issue. The runes that appear directly ahead of you are not wholly random, but rather subconscious decisions. Some rune users believe that you should only talk about issues, while others believe that asking questions is fine. Whatever way you use, remember to keep your query or concern in mind as you cast your runes. It’s important to remember that a rune reading isn’t about foretelling the future or providing conclusive answers. It’s all about looking for probable causes and consequences, as well as possible outcomes.

For more information on how to begin using the runes, check out How To Begin Using Runes here.